Scientific Advances - Destroying Memories: A New Approach to Treat Mental Health?

MU Article: Written by Erica (Natural Sciences, University of Cambridge, with a specialism in Psychology)

Our understanding of the psychological and neurological processes underlying mental health conditions is constantly improving. This allows us to continually update and improve treatment approaches, and sometimes even develop totally new ones. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition triggered either by experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares and severe anxiety, and these are often severe and persistent enough to have a significant impact on a person’s day to day life. PTSD can be considered a maladaptive memory disorder, and a radical new treatment approach has recently been developed to specifically target, and destroy, these maladaptive memories.

How is PTSD a maladaptive memory disorder?

There are many types of memory, each supported by different brain regions and circuitry. Two of these types are declarative memory: the what/where/when of an experience, and non-declarative memory: the emotional memories (such as of fear) associated with an experience. For more information about the different kinds of memory see Decode the Mind: Memory Explained — Minds Underground. Declarative memory is supported by a brain structure called the hippocampus, whereas emotional memories are controlled by the amygdala. These two structures respond very differently to the extreme stress experienced in a traumatic event: the strength of memory storage in the hippocampus decreases whereas the strength is significantly increased in the amygdala. Therefore, when someone undergoes a traumatic experience, they are left with an overly strong emotional memory (in this case of fear) that is not tied to a specific time or place. As a result, symptoms of PTSD can occur at any time, as they are not triggered by one particular cue. This can be maladaptive, meaning the memories can induce behaviour inappropriate to the situation, for example when an ex-veteran hears a car backfire and behaves as if they are reliving combat experiences.

How is it possible to erase a particular memory?

Profound advances in our understanding of memory have enabled us to develop a new treatment approach that attempts to target and destroy these maladaptive memories that underlie PTSD.

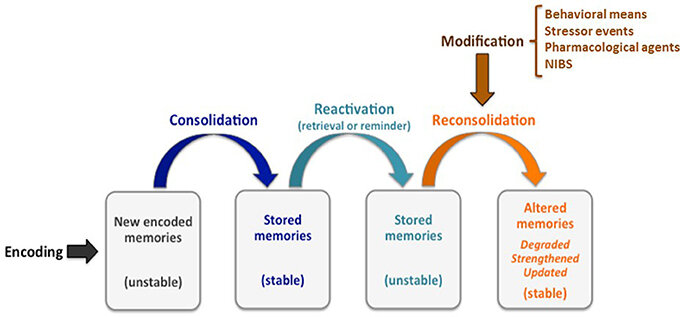

After a memory is formed, it needs to be converted from short-term to long-term memory or risk being immediately forgotten. The process by which memories are made to persist is known as consolidation, and involves structural changes to those neurons involved in forming the memory. It was previously thought that once a memory has been consolidated, these structural changes supporting memory storage were permanent. However, we now know that this is not the case. A memory that has previously been fully consolidated can be later reactivated or retrieved under certain conditions, and this retrieval destabilises the memory, making it vulnerable to modification. Previous structural changes are undone, and the memory must undergo another phase of structural changes to persist into the future - it must be reconsolidated. Theoretically, if you were to block these structural changes right after retrieval of a memory, you would block the reconsolidation process and thereby disrupt the memory.

It is thought that reconsolidation exists as a way for us to continually update our memories. When we retrieve some information about a memory, we open this memory in ‘edit mode’ and can update the memory in light of any new experiences we have had. It is important to note that reactivating a memory in such a way so that it becomes unstable (‘edit mode’) only happens under specific conditions of memory retrieval. Many labs have investigated what these conditions are, but it is generally believed to depend on introducing a small amount of new information, which needs to be incorporated into the memory.

The existence of this reconsolidation window, where it is possible to ‘edit’ a memory, offers a unique opportunity to interfere with the process of memory restabilisation, with the potential of weakening or even erasing the emotional expression from specific fear memories. An approach to treating PTSD by destroying the maladaptive fear memory therefore requires two things:

1) A way of reactivating the specific fear memory in such a way that it becomes unstable and requires reconsolidation

2) A way to prevent that memory reconsolidating

How has this been achieved in practice?

It was found fairly early on in reconsolidation research that a drug widely prescribed in humans to treat high blood pressure – propranolol - was able to prevent reconsolidation of fear memories in rats. Rats were first conditioned to find a particular trigger cue frightening. After this, if the fear memory was reactivated and propranolol was then given, the rats behaved as if they were no longer afraid of the frightening trigger cue, just as if they had never learned to be frightened of that cue in the first place. As propranolol was already known to be safe for use in humans, not long after these rat studies the drug was used on healthy human volunteers. These studies found that propranolol could also destroy fear memories in humans, but only if the memory had been made unstable by reactivation. These findings are especially important as they show that the rat findings can be extended into humans, which ultimately opens up this approach as a treatment for human patients.

In this new approach to treating PTSD, the aim is to selectively destroy the emotional/fear memory without touching the declarative memory. A patient should still be able to remember the details of their trauma, just they will not experience the overwhelming emotional response previously associated with that. It should be that the memories of a treated PTSD sufferer will be closer to those of someone who has undergone a similar trauma but not gone on to develop PTSD, than those of someone who has never undergone trauma.

In humans, we can test the extent that declarative memory is affected. Even though people who were given propranolol while a fear memory was reactivated were no longer afraid of a frightening trigger cue, they could still describe the relationship between a cue and the frightening outcome. It was just as if they knew why they should be afraid of the cue, but they were not. This strongly suggests that propranolol can successfully target emotional memories, leaving declarative ones intact.

Several labs worldwide have conducted small scale clinical trials of memory destroying treatments for PTSD using propranolol and so far, they have had extremely promising results, with many patients showing a steep decline of fear symptoms after treatment. These trials still require replication on a larger scale, but they are very encouraging of the possibility of treating PTSD by destroying memories.

What other conditions could this approach help?

PTSD is by no means the only condition which has a strong memory component and therefore there is no reason why this approach of destroying memories should be limited to PTSD. For example, sufferers of addiction are significantly more likely to relapse if presented with an environmental cue which they have previously associated with drug abuse. Therefore, selectively destroying these memories could help an addict stay sober. Research into the psychological and neurochemical mechanisms of drug memory reconsolidation suggests that its disruption could potentially provide a form of anti-relapse treatment for drug addiction.

This new memory destruction approach has the potential to revolutionise the way in which we treat certain mental health conditions and could have immensely positive impacts on people’s lives. Huge scientific advancements like these are not possible without staying up to date with exciting developments in underlying scientific theory. Keeping up with current research in one’s topics of interest, especially those outside the curriculum, is extremely useful preparation for those interested in future degrees and careers in STEM subjects.

Interested in further Psychology ‘Beyond the Syllabus’ exploration?

Stay updated by reading high-level articles such as scientific journal, Nature’s, papers on the brain (link)

Discuss scientific developments with fellow aspiring scientists as part of our Senior STEM Club

Customise a Psychology course, hosted by an Oxbridge-educated Psychology mentor

Applying to university/ Oxbridge? Check out our sister division, U2 Tuition, for details on support for each application component

Tuition sessions from £70/h.